Racial differences in response to asthma therapies, and other AsthmaNet lessons

African Americans have higher rates of serious asthma attacks, hospitalizations, and asthma-related deaths than whites. Now, a large multicenter study of African Americans with poorly controlled asthma finds that one size doesn’t fit all when it comes to common asthma treatments. Results appear in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

The randomized study had 574 participants — about half aged 5 to 11, and half 12 years and older. Based on genetic testing, they were of 80 percent African ancestry, on average. Most asthma studies have underrepresented such patients. All had symptomatic asthma at the start of the study, despite receiving adequate low doses of inhaled corticosteroids.

About half of the children 5-11 (46 percent) responded better when long-acting bronchodilators (to open up the airways) were added to their asthma treatment. Another 46 percent did better with a higher dose of inhaled corticosteroids.

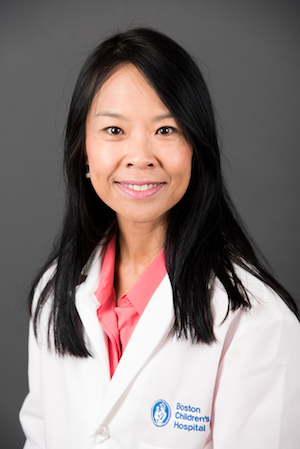

“This is different than what was seen in white children, in whom increasing inhaled corticosteroid doses seemed to provide the most benefit,” says Wanda Phipatanakul, MD, MS, director of the Asthma Clinical Research Center at Boston Children’s Hospital. “We now know there can be racial differences in how we manage asthma and what treatment provides a better response. We need more study to help target and personalize our approach.”

AsthmaNet: Refining what we know about asthma

The study is the latest to be released by AsthmaNet, a research network established in 2009 by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Phipatanakul has led Boston Children’s participation in a series of AsthmaNet studies, also published in NEJM.

Earlier this year, the Steroids in Eosinophil Negative Asthma (SIENA) trial studied patients with mild persistent asthma. It found that those with a low sputum eosinophil level responded similarly to either mometasone or tiotropium when compared with placebo. In contrast, patients with high eosinophil counts, indicating increased airway inflammation, tended to do better with mometasone.

A 2018 study in children with persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma asked whether quintupling the dose of daily inhaled steroids at the first signs of loss of asthma control would reduce severe asthma exacerbations. It did not, nor did it improve other asthma outcomes. Moreover, there were signs that the ramped-up steroid dose compromised children’s growth.

Finally, a 2016 study compared ibuprofen and acetaminophen head to head in children with asthma. Its findings ruled out a link between acetaminophen and asthma exacerbations.

Current studies

Taking concepts learned from the AsthmaNet work, Phipatanakul has received independent funding for two major trials centered at Boston Children’s. The multicenter Preventing Asthma in High Risk Kids (PARK) Study is investigating whether early blockade of IgE with omalizumab (Xolair) will prevent asthma from developing in 2- to 4-year-olds with allergy.

The Investigating Dupilumab Effects in Asthma (IDEA) trial will group participants based on a genetic mutation that is associated with severe asthma, affecting the IL-4 pathway. Dupilimab acts directly on this pathway. “We hypothesize that patients with two copies of the mutant allele will respond more favorably to dupilumab than those without the allele, or with a single copy,” Phipatanakul says.

For information on these trials and other ongoing studies, contact the Asthma Clinical Research Center (857-218-5336 or asthma@childrens.harvard.edu).

Related Posts :

-

BRD7 research points to alternative insulin signaling pathway

Bromodomain-containing protein 7 (BRD7) was initially identified as a tumor suppressor, but further research has shown it has a broader role ...

-

When diagnosis is just the first step: The Brain Gene Registry

Through advances in genetic sequencing, many children with rare, unidentified neurodevelopmental disorders are finally having their mysteries solved. But are ...

-

Engineered cartilage could turn the tide for patients with osteoarthritis

About one in seven adults live with degenerative joint disease, also known as osteoarthritis (OA). In recent years, as anterior ...

-

Surgery beats sclerotherapy for rectal prolapse in children ages 5 and older

Rectal prolapse — the protrusion of the lining of a child’s rectum through the anal sphincter — can occur for many ...