Gene therapy halts progression of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy in clinical trial

Adrenoleukodystrophy — depicted in the 1992 movie “Lorenzo’s Oil” — is a genetic disease that most severely affects boys. Caused by a defective gene on the X chromosome, it triggers a build-up of fatty acids that damage the protective myelin sheaths of the brain’s neurons, leading to cognitive and motor impairment. The most devastating form of the disease is cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (CALD), marked by loss of myelin and brain inflammation. Without treatment, CALD ultimately leads to a vegetative state, typically claiming boys’ lives within 10 years of diagnosis.

But now, a breakthrough treatment is offering hope to families affected by adrenoleukodystrophy. A gene therapy treatment effectively stabilized CALD’s progression in 88 percent of patients, according to clinical trial results reported in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study was led by researchers from the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and Massachusetts General Hospital.Read the press release about the clinical trial results.

“Since it was first described 100 years ago, adrenoleukodystrophy has robbed the function of children who, up until the disease’s onset, had been developing normally,” says Florian Eichler, MD, co-lead author on the study and the director of the Leukodystrophy Service at Massachusetts General Hospital. “These are children who have been growing and thriving, and then suddenly, their parents witness this devastating decline that starts with personality changes and then progresses to motor problems and loss of their ability to walk and talk.”

Halting adrenoleukodystrophy in its tracks

In the clinical trial, sponsored by bluebird bio, 15 of 17 patients had stable neurologic functioning more than two years after receiving the gene therapy. The ongoing trial, one of the largest gene therapy trials targeting a single-gene disease to be published to date, has received regulatory approval to expand its number of patients.

“Although we need to continue to follow the patients to determine the long-term outcome of the gene therapy, so far it has effectively arrested the progress of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy in these children,” says David A. Williams, MD, chief scientific officer and senior vice-president for research at Boston Children’s Hospital, president of Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and the lead author of the study. “This is a devastating disease, and we are all quite grateful that the patients and their families chose to participate in the trial.”

The treatment leverages bluebird bio’s proprietary Lenti-D gene therapy to deliver the functional gene to patients’ stem cells in the laboratory. Now, bluebird bio is engaged in ongoing discussions with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European regulators on their plans to bring the therapy to market.

How the gene therapy works

Adrenoleukodystrophy is caused by a mutation to a gene on the X chromosome called ABCD1, which controls the body’s production of an enzyme called ALD protein that normally breaks down fatty acids. When a mutation to the ABCD1 gene interrupts the function of ALD protein, fatty acids build up and cause a degenerative breakdown of the protective myelin sheaths of the nerves. The fatty acids are also toxic to cells in the adrenal glands, small organs above the kidneys that produce hormones, which results in hormonal imbalances.

Newborn screening and childhood genetic testing can identify young boys who have the defective ABCD1 gene before symptoms of adrenoleukodystrophy appear, creating a small window of opportunity to prevent the disease’s degenerative effects before they begin to irreversibly accumulate.

Until now, stem cell transplantation — using cells donated by another person — has been the only known effective therapy for CALD. It usually works best with a disease-free, matched sibling donor, which fewer than one-quarter of CALD patients have.

Read the full, detailed report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“There are two great advantages to gene therapy,” Williams says. “The first is that patients don’t have to wait to find a donor match. The second is that, because we use their own, gene-modified stem cells, there’s no risk of graft-versus-host-disease and the patients do not require any immunosuppression drugs, which can have very significant, even fatal, side effects.”

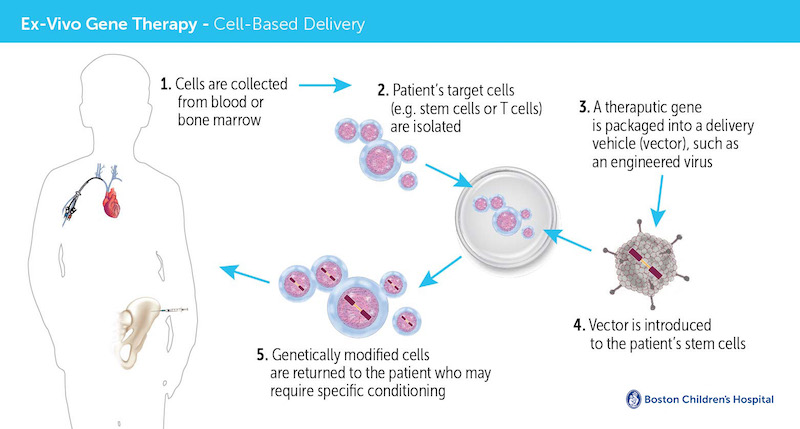

To perform the gene therapy, clinicians first collect a patient’s blood stem cells, which give rise to all mature blood cells. In a highly-specialized laboratory that contains a clean room for preparation of medicines, a viral vector is used to insert a correct version of the faulty ABCD1 gene into the patient’s stem cells. Then, after the patient receives chemotherapy to make room for the genetically-altered blood stem cells in the bone marrow, the cells are infused back into the patient’s bloodstream via an intravenous line.

“This treatment results from more than two decades of investment in basic gene therapy research by the NIH and others,” Williams says. “It really demonstrates that research funding is essential to developing the next generation of therapies for devastating childhood diseases.”

Gene therapy in the real world

“In my clinic, the impact of this trial has been phenomenal,” Eichler says. “Boys without a donor match for stem-cell transplant were often passing away within a year or two of their diagnosis. Now, with early diagnosis and gene therapy, these boys are living longer and some are thriving enough to play sports and participate in other normal day-to-day activities.”

Christine Duncan, MD, co-lead author on the study and a pediatric hematologist/oncologist at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, has also witnessed first-hand the impact that gene therapy has had on boys with CALD. At the latest follow-up, all patients who participated in the clinical trial were expressing functional ALD protein, which their bodies had been unable to produce prior to gene therapy.

The ALD gene therapy trial is part of a growing portfolio of pediatric gene therapy trials at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center that also includes clinical trials for X-linked severe combined immune deficiency (“bubble boy” disease), chronic granulomas disease, a recently completed trial for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and the use of gene therapy to treat some types of childhood leukemia using CAR T-cells.

In addition, the FDA has just approved a ground-breaking study at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center for the use of gene therapy to cure sickle cell disease.

Learn more about the CALD clinical trial and how to enroll.

Related Posts :

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity and ...

-

Treatment for the vision condition achromatopsia helps Aiden embrace the outdoors

A lot of things excite 10-year-old Aiden Flaherty: drums, soccer, skiing, video games. But lately, he’s also found joy ...

-

Sickle cell gene therapy and boosting fetal hemoglobin: A 75-year history

Ed. Note: This post updates an earlier post from 2018. In a landmark decision today, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ...

-

Here’s how genetic vision testing can help your family

At least 600 of the roughly 20,000 genes in the human body are needed for normal eyesight. Changes in those genes can ...