Good early results with gene therapy for rare immune deficiency

Brenden Whittaker, a college student in Ohio, has been caught off guard by his good health. Since he was young, a rare immune deficiency known as chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) had left him vulnerable to life-threatening infections. He was used to going in and out of the hospital, and then hooking up to an IV several times a day at home to receive antibiotics and antifungal drugs.

Over time, the infections got worse, and by 2009, Brenden was planning his funeral. He was 15.

“It was part of my mentality, not knowing how long I was going to live,” he says.

One infection was so bad that Brenden had part of his right lung removed — a last-ditch treatment. Another led to removal of part of his liver. He had to repeat his junior year of high school; later, he was forced to drop out of college.

“It just wasn’t feasible between all the doctor appointments,” Brenden says. “I couldn’t do the homework and the reading that was required.”

It was part of my mentality, not knowing how long I was going to live.

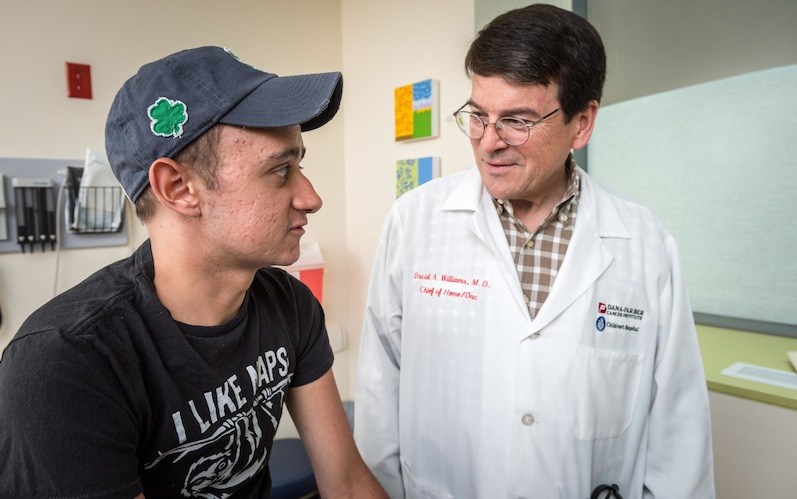

December 2015 was when Brenden’s trajectory changed. At 22, he came to Boston Children’s Hospital and became the first person in the U.S. to receive a genetic therapy for CGD under a new international trial. And so far it has worked.

“I’m still adjusting,” says Brenden. “Trying to decide what to do with the rest of my life, knowing it is going to be longer than a month from now, is something I’m not totally used to.”

Strengthening the immune response in CGD

Brenden’s case is one of nine reported this week in Nature Medicine. The trial also involved the University of California Los Angeles, the Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, and the National Institutes of Health.

The CGD gene therapy treatment is the product of a decades-long scientific journey, largely at Boston Children’s Hospital, that started with the development of a better diagnostic test for CGD and the cloning of the relevant gene.

In CGD, various mutations prevent neutrophils, white blood cells that ingest bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms, from completing the final step: killing them. The gene therapy restores a healthy copy of gp91phox, part of a protein complex needed to kill the germs.

The treatment required Brenden to stay at Boston Children’s for about six months. He first received medications to boost his blood stem cells, which were collected from his bloodstream and then isolated in the lab. The cells were exposed to an engineered virus that went inside the cells and inserted a healthy copy of the gene. The engineered virus was designed to “turn on” gp91phox only in a few cell types, including neutrophils.

Meanwhile, Brenden received chemotherapy to kill off his own blood stem cells to make room for the treated cells, which were then infused back into his blood. It was a rigorous course of treatment, not without its own risks.

How gene therapy for CGD works:

“He was brave to make a decision to try something not yet known to be effective,” says Sung-Yun Pai, MD, a senior stem cell transplant attending physician and co-director of the Gene Therapy Program at Boston Children’s. She has been following Brenden since 2016. “We’re super happy that he has had a great outcome.”

Keeping CGD at bay

Within a month, Brenden’s treatment team, led by David Williams, MD, chief scientific officer at Boston Children’s, saw early signs that the treatment was working. “The gene was being expressed, and a portion of his neutrophils were functioning, responding to stimulation in the lab,” says Pai. “After a year, we started really believing it that it was going to stay at that level and not go down.”

While only about 10 to 15 percent of Brenden’s cells neutrophils were genetically corrected, that appears to be enough to prevent the severe infections. (The protocol has since been enhanced to increase the amount of neutrophils corrected.)

When Brenden was discharged, as a matter of precaution, he continued on one IV antibiotic, two IV antifungal drugs, and two oral antibiotics. For three months, he couldn’t leave the house unless wearing a mask. By 18 months, he had been weaned off all antimicrobials, says Pai.

Most patients in the clinical trial have also done well. Two patients died early on from underlying complications of CGD before the benefit of gene therapy was realized. But of the remaining seven, six, including Brenden, have had no new CGD-related infections 12 months out from treatment. Six, including Brenden, no longer need antibiotic prophylaxis, with tests showing that the healthy gene had remained at stable levels in their neutrophils.

“While it is still too early to talk about permanent cure, the data so far are quite encouraging that the effectiveness is stable over time,” says Williams, who founded Boston Children’s Gene Therapy Program in 2010.

A new lease on life

The gene therapy team will follow Brenden and the other patients to the 15-year mark to ensure that the treatment is safe and that its effects are lasting. In the meantime, Brenden is back in college in Columbus, Ohio, and is thinking of pursuing either health sciences or nursing. He also works part-time as a bartender at a country club, while making plans for his financial and educational future.

“I’m still in shock that it’s worked for this long,” he says. “Before, it was, ‘am I going to be alive next week’? Now, barring an act of God, I’m going to be alive for the foreseeable future.”

Learn more about gene therapy for CGD.

Related Posts :

-

Thanks to Carter and his family, people are talking about spastic paraplegia

Nine-year-old Carter may be the most devoted — and popular — sports fan in his Connecticut town. “He loves all sports,” ...

-

Tough cookie: Steroid therapy helps Alessandra thrive with Diamond-Blackfan anemia

Two-year-old Alessandra is many things. She’s sweet, happy, curious, and, according to her parents, Ralph and Irma, a budding ...

-

Unique data revealed just when Mickey’s heart doctors could operate

When Mikolaj “Mickey” Karski’s family traveled from Poland to Boston to get him heart care, they weren’t thinking ...

-

Genomic sequencing transforms a life: Asa’s story

Asa Cibelli feels like he’s been reborn. The straight-A middle schooler plays basketball and football, does jiu jitsu, is ...