COVID-19 and a serious inflammatory syndrome in children: Unpacking recent warnings

On April 27, an alert circulated from the U.K. about multi-system inflammatory disease in children with COVID-19, based on a small rise in the number of critically ill children with this illness in England. Picked up by multiple media outlets, the alert cited features of toxic shock syndrome and incomplete Kawasaki disease, with some children experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms and cardiac inflammation. The New York City health department soon followed with its own alert.

The CDC is now calling this emerging syndrome “multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).” On May 2, the International PICU-COVID-19 Collaboration, coordinated by Jeffrey Burns, MD, MPH, chief of Critical Care Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, convened a Zoom conference to compare notes. Pediatric experts in intensive care, cardiology, rheumatology, infectious disease, and Kawasaki disease reviewed data from several dozen cases in Europe and the U.S., offered guidance for clinicians, and laid out an agenda for research.

Read about the latest findings on MIS-C, recently reported in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Key take-homes

Two things are clear about this still-mysterious pattern of illness. First, thus far it is rare. But second, clinicians who suspect a case should consult promptly with pediatric infectious disease, rheumatology, or critical care specialists. Because some children get sicker rapidly, they should be cared for in hospitals with tertiary pediatric/cardiac intensive care units. Their cases should be discussed with pediatric specialists in infectious disease, rheumatology, and cardiology to anticipate and manage aspects of the illness.

MIS-C: An emerging picture

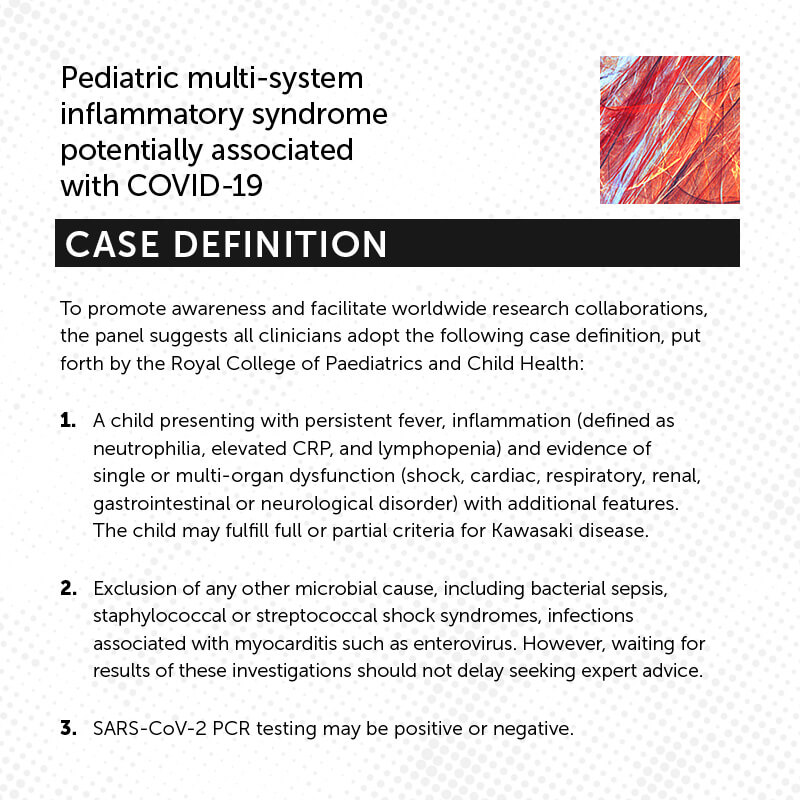

During the May 2 conference, panelists described a syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19, marked by persistent fever, inflammation, poor function in one or more organs, and other specific clinical and laboratory features not attributable to other infections (see Case Definition). Many affected children were hospitalized and some required intensive care due to a clinical picture consistent with shock.

Some children presented with some or all features seen in Kawasaki disease, an illness of children that can result in enlargement or aneurysms of the coronary arteries. Features observed included fever, rash, conjunctivitis, swollen hands and feet, cracked lips, a swollen or bumpy tongue resembling the seeds on a strawberry, and an enlarged lymph node in the neck. Some children had clinical and laboratory signs of cytokine storm syndrome, an exaggerated systemic immune response that has caused organ damage in adults with COVID-19.

Finally, many children had coagulopathies; cardiac dysfunction; diarrhea, abdominal distension, and other GI symptoms (with some children having positive stool tests for SARS-CoV-2); or acute kidney injury. Respiratory symptoms were not always a prominent feature.

“We could be dealing with several phenotypes on a spectrum,” says Boston Children’s Hospital rheumatologist Mary Beth Son, MD, who was one of the conference panelists. “In some cases, children present with shock and some have features of Kawasaki disease, whereas others may present with signs of cytokine storm. In some geographic areas, there has been an uptick in Kawasaki disease cases in children who don’t have shock.”

The U.S. cases to date have been mainly in East Coast cities, with some in the Midwest and South. Of note, an uptick has not been observed on the West Coast, or in Japan and Korea, where a different strain of SARS-CoV-2 is believed to predominate.

To date, most children affected have done well. Treatments have included anticoagulation, IV immunoglobulin, IL-1 or IL-6 blockade, and corticosteroids. Some children have only needed supportive care.

Why are cases of COVID-related inflammation emerging now?

Of note, not all children with this inflammatory syndrome tested positive for COVID-19. PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 was often negative, and tests for antibodies were sometimes but not always positive. While the tests themselves may have had varied accuracy, the fact that PCR-negative patients sometimes positive for antibodies suggests that inflammatory complications were delayed, occurring when the virus was no longer detectable on nasal swabs.

“We have these clusters of illness where we can’t say it’s caused by COVID, but clearly it’s temporally related,” says Son.

Why these cases are emerging only now, and what is causing them, is still a mystery. Panelists speculated that an acquired immune response to COVID activates an inflammatory process in genetically susceptible children. But other mechanisms are possible as well.

“If you look at the curves, COVID-19 has plateaued, but there’s an exponential rise in this secondary type of shock syndrome,” says cardiologist Jane Newburger, MD, MPH, an international expert on Kawasaki disease who was also on the May 2 panel. “It is even possible that the antibodies that children are making to SARS-CoV2 are creating an immune reaction in the body. Nobody knows.”

Clinical work-up of multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children

In its consensus statement, the international PICU panel offered the following guidance for clinicians encountering potential cases of MIS-C:

Follow-up: While not all may become severely ill, children with unexplained fever and evidence of inflammation (elevated C-reactive protein or white blood cell count) should be carefully followed to detect potential progression of disease.

Laboratory tests: Evaluation should include measurement of sequential inflammatory markers, including complete blood count/differential, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; coagulation parameters including D dimer and ferritin; liver function markers; and a cytokine panel. Children should have antibody testing in addition to PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2, since many children are antibody-positive even when PCR-negative.

Echocardiography: Children with this syndrome should have serial echocardiograms including detailed assessment of the coronary arteries. Many to date have been found to have low heart function, and some have enlargement of the coronary arteries. Children with serious cardiac complications should be followed longer-term.

A call for more research on MIS-C

The panelists pointed to an urgent need to better understand this emerging COVID-associated illness pattern in children — how children’s immune systems are responding, what genetic risk factors they may carry, and why there’s such a range of presentations. They urge clinicians to enroll children in research protocols that include obtaining serum or plasma samples, DNA, and RNA studies for biobanking.

They also call on government and other health agencies to invest immediately in clinical trials, as well as data integration drawing on registries of children with COVID-19 and children with the new inflammatory syndrome.

“The best evidence to date, from the CDC and this International Collaboration, is that children rarely become critically ill from COVID-19, or from MIS-C,” says Burns. “Our major objective is to alert clinicians to this clinical presentation, to ensure that these children get treated by pediatric specialists who pursue the appropriate clinical work-up, and to see that they are enrolled in integrated data registries and clinical trials that will promote evidence-based care and a better understanding of this disorder.”

More on Boston Children’s response to COVID-19 and COVID-19 research at the hospital.

Related Posts :

-

Four things you should know about MAPCAs treatment

As the first grandchild in her family, Hannah Homan is in demand for frequent visits. She was also the focus ...

-

Treating MAPCAs with unifocalization surgery and cardiology care

Children born with a rare form of tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) face a challenging type of congenital heart ...

-

A safe, pain-specific anesthetic shows preclinical promise

All current local anesthetics block sensory signals — pain — but they also interrupt motor signals, which can be problematic. For example, ...

-

After surgeries to treat HLHS, Carter is healthy and happy at home in Florida

Carter Miller loves action. The 4-year-old Florida resident enjoys riding on golf carts and flying high on swing sets. ...