Drug-eluting contact lens offers hope in glaucoma

Daily medicated eye drops are the first line of treatment for glaucoma, the leading cause of irreversible blindness. The drops relieve pressure in the eye, a significant risk factor for glaucoma. But they’re not ideal: their delivery is imprecise, they can cause stinging and burning and patients often struggle to administer them. Adherence is poor: in one study based on insurance claims data, nearly half of patients who had filled a glaucoma prescription stopped topical glaucoma therapy within six months.

Engineered contact lenses dispensing glaucoma medication gradually could vastly improve adherence, helping hang onto their eyesight longer. In a pre-clinical study of glaucoma published online this week in the journal Ophthalmology, slow-release lenses lowered eye pressure at least as well as daily eye drops containing the drug latanoprost — and, in a higher-dose form, possibly more so.

“We found that a lower-dose contact lens delivered the same amount of pressure reduction as latanoprost drops, and a higher-dose lens, interestingly enough, had better pressure reduction than the drops in our small study,” says Joseph Ciolino, MD, an ophthalmologist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, the study’s first author. “Based on our preliminary data, the lenses have not only the potential to improve compliance for patients, but also the potential of providing better pressure reduction than the drops.”

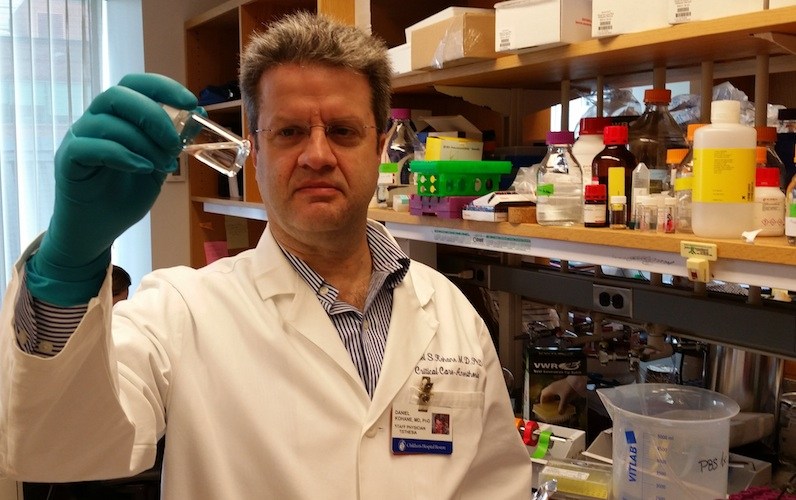

Contact lenses have been studied as a means of ocular drug delivery for nearly 50 years, yet many have failed, dispensing the drug too quickly. Some earlier designs involved simply soaking the lens in the drug solution, and released it within hours. Daniel Kohane, MD, PhD, director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children’s Hospital and senior author on the paper, took the problem to his lab.

Kohane designed a lens whose center is ringed with a thin polymer film encapsulating latanoprost. The center and rim of the lens are left clear, allowing for normal visual acuity, breathability and hydration.

“Instead of taking a contact lens and allowing it to absorb a drug and release it quickly, our lens uses a polymer film to house the drug,” he says. “The film has a large ratio of surface area to volume, allowing the drug to release more slowly.”

Kohane and Ciolino showed in a 2013 study that the lens is capable of delivering medication continuously for one month in a rabbit model.

Supported by a grant from the Boston Children’s Hospital Technology Development Fund, Ciolono and Kohane assessed the contact lens in four monkeys with glaucoma. The lens with lower doses of latanoprost reduced intraocular pressure as effectively as the eye drop version of the medication.

The higher-dose lenses performed even better than the drops. Further study is needed to confirm that finding, as well as tolerability of the lenses over time.

“If we can address the problem of compliance, we may help patients adhere to the therapy necessary to maintain vision in diseases like glaucoma, saving millions from preventable blindness,” says Ciolino. “This study also raises the possibility that we may have an option for glaucoma that’s more effective than what we have today.”

The lenses can be made with no refractive power or with the ability to correct nearsighted or farsighted eyes. The researchers are currently designing clinical trials to determine the lenses’ safety and efficacy in humans. “Right now we’re looking at it as a weekly-wear lens,” says Kohane.

Kohane hopes to commercialize the lenses and is also studying the polymer film as a means of delivering steroids, corneal anesthetics, antibacterial drugs and antifungal drugs into the eye. “It can be applied to a broad range of diseases,” he says.

For inquiries about the technology, contact Boston Children’s Technology Innovation and Development Office (TIDO) at tido@childrens.harvard.edu.

Related Posts :

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...

-

A new druggable cancer target: RNA-binding proteins on the cell surface

In 2021, research led by Ryan Flynn, MD, PhD, and his mentor, Nobel laureate Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, opened a new chapter ...

-

Modeling urinary tract disorders on a chip: Zohreh Izadifar

When a new tissue sample arrives from the Department of Urology, the Boston Children’s Hospital lab of Zohreh Izadifar, ...

-

Could a pill treat sickle cell disease?

The new gene therapies for sickle cell disease — including the gene-editing treatment Casgevy, based on research at Boston Children’s ...