Matthew, the ‘wee marvel’: One of the first ALD gene therapy recipients

When the Elliott brothers are asked how many siblings they have, they always say, “four.” It’s a way of honoring the memory of their eldest brother, Marc, who died in 2010 from adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD).

ALD is a degenerative condition that destroys the protective sheath surrounding the brain’s neurons. Gradually, as the disease progresses, symptoms grow worse, including blindness, deafness, and loss of muscle control. Without effective treatment, the disease is fatal.

Matthew was just a baby when Marc died, and the two youngest, Lee and Alex, never met Marc. Yet the connection runs deep.

Their story began in a hospital waiting room in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, 80 miles west of Belfast, a short walk from Adel and Damien Elliott’s home. Their 4-year-old, Marc, had been ill on- and off-again with a vomiting bug since he was a toddler. On this day, they were summoned to the hospital for genetic testing. “I just knew something bad was coming,” says Adel.

Families affected by rare diseases often suffer through a long and frustrating diagnostic odyssey, ending with devastating news about their child’s condition and prognosis. In this case, the Elliotts came to understand that Marc’s disease would lead to his death. Adel recalls, “I asked, ‘Is this going to kill him?’ The nurse looked at me and said, ‘I’m so sorry.’”

The Elliotts traveled to Belfast and then Bristol, England, for more testing. An MRI showed lesions (damage) on Marc’s brain, confirming the ALD diagnosis. But that wasn’t all. ALD, they would learn, is a genetic disorder, carried by women and passed to their children, mostly affecting boys. Their 2-week-old son, Matthew, would need to be tested too.

Just three days after his christening, Matthew was found to have the same gene mutation as his big brother. “When your heart has been broken to pieces, you don’t expect it could possibly break anymore,” Adel says.

With limited treatment options for ALD, doctors recommended a bone marrow transplant for Marc, using healthy blood stem cells from a donor to replace his diseased bone marrow. Although they were able to find a suitable donor, his body rejected the transplant. He began slowly slipping away. He lost his peripheral vision and most of his mobility, “but he never lost his smile,” Adel says. On Aug. 14, 2010, the 6-year-old died in his parent’s arms.

It turns out the heart can break to pieces — again and again.

To focus on Matthew’s survival, the Elliotts buried their grief. “We could not rest,” Adel says. They traveled to Belfast for regular checkups and routine MRIs and held their breath as they listened to the doctors say, “unchanged.” They started Matthew on a concoction of cooking oils — made famous in the 1992 film “Lorenzo’s oil” — aimed at reducing the very-long-chain fatty acids that accumulate in ALD. And all the while, they began to think about expanding their family. Would it be possible? By conceiving through in vitro fertilization, it would. They could have the embryos tested to make sure their children didn’t carry the disease.

A new gene therapy

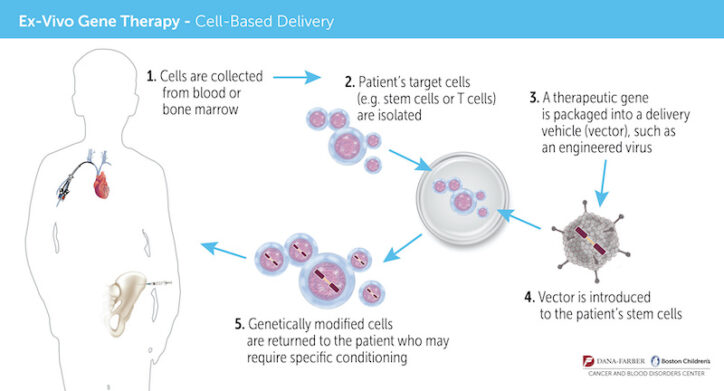

Meanwhile, an international research team, led by Dr. David Williams, chief of Hematology/Oncology at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Dr. Florian Eichler, who directs the Center for Rare Neurological Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, had developed a study protocol aimed at halting the progression of ALD using gene therapy. Instead of taking cells from a donor, bone marrow would be taken from the boys themselves, treated with a virus carrying the gene for the ALD protein, then reinfused.

“There are two great advantages to gene therapy,” Dr. Williams says. “First, patients don’t have to wait to find a donor match. Second, because we use their own, gene-modified stem cells, there’s no risk of graft-versus-host-disease, and the patients do not require any immunosuppression drugs, which can have very significant, even fatal, side effects.”

The Elliotts traveled to Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, a long-time collaborator of Boston Children’s, to learn more about the treatment, which at the time was still experimental. (It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration on September 2, 2022.) Further testing would be needed, but Matthew appeared to be a strong candidate as long as he didn’t have a sibling who was a bone-marrow match, which would disqualify him from the study. The London clinical trial wasn’t up and running yet, but the one in Boston would be open that summer.

“This was all predetermined — just in case,” says Adel. “We had no idea if gene therapy would actually work. It was a huge risk.”

Hope amidst heartache

The day after Matthew’s 4th birthday, on April 25, 2013, Adel had an appointment with her midwife. She was nine months pregnant with her third son, Lee. The phone rang. There were changes in Matthew’s MRI. “It was like déjà vu, because I was nine months pregnant with Matthew when Marc took sick,” she says.

Unless Matthew had a 10 out of 10 bone-marrow match, the Elliotts weren’t willing to travel the transplant route again. But at only nine days old, their son, Lee, was tested to see if he would be a suitable donor.

Meanwhile, as Adel waited for the results in the maternity unit, her own mother, who recently had been diagnosed with glioblastoma, was having brain surgery in another wing of the same hospital.

Lee was not a match after all: a moment of relief. Matthew could now be considered for the clinical trial. Within days, the Elliotts were on a call with Colleen Dansereau, director of Clinical Operations for the Boston Children’s Gene Therapy Program. “She told us, ‘See you this weekend,” Adel recalls.

Four weeks and numerous tests and doctor appointments later, Colleen called to deliver the news. “Matthew is eligible for the trial! He will be our first patient.”

Elated, the Elliotts returned home for two weeks, and then headed back to Boston for six months. Matthew’s blood stem cells were collected and, in a highly-specialized laboratory, treated with a viral vector to insert a correct version of the faulty gene. Then, he received chemotherapy to make room for the genetically-altered stem cells.

Finally, on October 25, 2013, under the care of Boston Children’s gene therapy team and Dr. Eichler, Matthew received the gene therapy treatment: a single infusion that everyone hoped would prevent ALD from affecting his brain. “I messaged home, this is the start of Matthew’s new life,” Adel says. “And my family started FaceTiming me. I thought it was because of this exciting news. It wasn’t. My mom had died at the exact same moment Matthew was given life.”

Matthew’s future

Nearly nine years have passed. Matthew, now 13, is playing soccer and thriving — with no sign of disease activity. “He sailed through gene therapy,” says Adel. “He was a wee marvel.”

Every July, the family celebrates Marc’s birthday. “He’s very much a part of our lives,” Adel says.

Only recently, prompted by questions from his brother, Lee — “Why does Matthew have to take medicine? Why is he going to the doctors?” — Matthew also began asking questions. “Is this not normal? Doesn’t everybody do this?”

“No,” said Adel. “They don’t.”

Matthew paused for a few moments, “I don’t want to die.”

Adel reassured him, “You’re not going to die.”

“But Marc died,” he said.

It was the first time Matthew had ever made the connection he had the same illness as Marc.

That same week, the Elliotts returned to Great Ormond Street Hospital for a follow-up appointment. Adel encouraged Matthew to ask the doctors any questions he might have.

“When will I be cured?” he asked.

Adel still remembers how they looked at Matthew, empathetically, and what they said to him, “We honestly can’t answer that, but as long as you’re here, we’re here. We’re learning from you every day, so keep living your life the way you are.”

Gene therapy now available for ALD

Now that the FDA has approved the gene therapy, called SKYSONA®, Boston Children’s is collaborating with Dr. Florian Eichler at Massachusetts General Hospital to offer it to boys with cerebral ALD who are not yet experiencing symptoms. Studies indicate that when gene therapy is given early enough, it can halt the decline in brain function caused by the disease. A long-term follow-up study is tracking the children’s progress over time.

For more information, contact gene.therapy@childrens.harvard.edu.

Learn more about the Gene Therapy Program at Boston Children’s.

Related Posts :

-

A rebirth in Boston: Gene therapy turns 10

Lea la versión en español. Dec. 17 marks a decade since Agustín Cáceres was “renacido” — reborn. That’...

-

Gene therapy’s future may be all about the bases

Gene therapy offers the possibility of a cure for many genetic disorders, especially those involving a single gene. The first ...

-

After decades of evolution, gene therapy arrives

As early as the 1960s, scientists speculated that DNA sequences could be introduced into patients’ cells to cure genetic disorders. ...

-

Unique data revealed just when Mickey’s heart doctors could operate

When Mikolaj “Mickey” Karski’s family traveled from Poland to Boston to get him heart care, they weren’t thinking ...