Arthritis drug reduces rates of acute graft-vs-host disease after bone marrow transplant

The immune-suppressing drug abatacept, currently used for rheumatoid arthritis, could make bone marrow transplant safer, report researchers at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. The phase 2 randomized, multi-center clinical trial, the largest to date, appears in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Abatacept (brand name ORENCIA) reduced rates of severe, acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), in which T cells in the donor bone marrow “see” the recipient’s healthy cells as foreign and attack them. It also boosted rates of survival without acute GVHD or relapse.

Update: In August 2021, the Food and Drug Administration granted abatacept priority review for prevention of moderate-to-severe acute GVHD in patients age 6 and older receiving bone marrow transplants from unrelated donors.

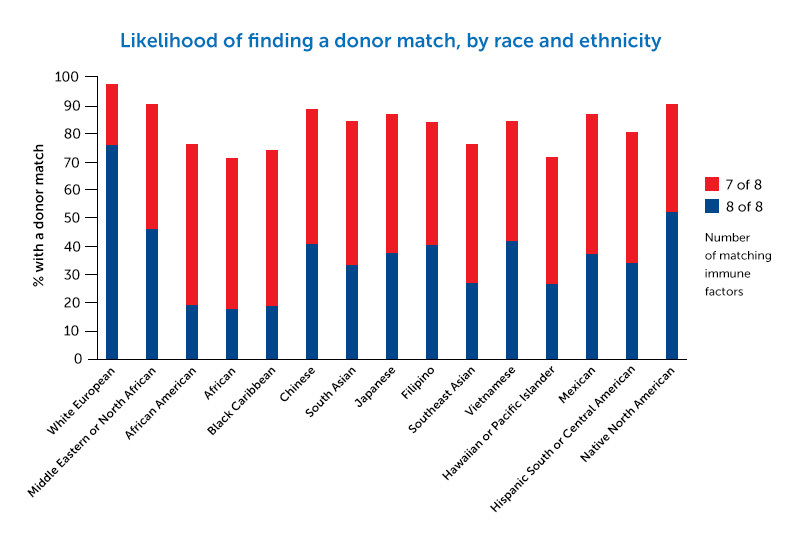

The promising findings could open up bone marrow transplant as an option for many more patients with cancer or blood disorders — especially when a full tissue-type match cannot be found. Lack of a full match is a particular problem for people of color and ethnic minority populations.

“One of the great tragedies is when a bone marrow transplant succeeds in curing a patient’s leukemia, but the patient dies from complications of the transplant,” says study leader Leslie Kean, MD, PhD, who directs Pediatric Stem Cell Transplant at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s. “I see this as the ‘democratization’ of transplant: leveling the playing field.”

Enabling bone marrow transplant

Severe, acute GVHD is fatal in up to half of patients. GVHD risk is lowest when donor and recipient match on 8 of 8 immune factors known as human leukocyte antigens (HLA). But if the match is just 7 of 8, the risks of severe, acute GVHD and associated death rise dramatically. This “7/8” group may stand to benefit most from abatacept.

If we can make these transplants safer, we would have the ability to offer them to many more patients.” — Leslie Kean

“Abatacept has now been shown, in patients with multiple diseases, to significantly increase the safety of transplants from donors that are HLA mismatched,” says Kean. “No other approach for GVHD has shown this substantial a difference in these very high-risk transplants.”

Abatacept and GVHD

The trial enrolled adults and children receiving bone marrow transplants for leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and other blood cancers. One study arm randomized 142 patients and donors, matched for 8 of 8 HLA factors, to receive either abatacept or placebo. Both groups also received standard GVHD prevention drugs. In the second arm, 43 patients with a donor match on 7 of 8 factors all received abatacept. The researchers compared them with a historical control group treated with the standard prevention regimen alone.

In the 8/8 group, 6.8 percent of patients given abatacept developed severe acute GVHD during the first 180 days after transplant, versus 14.8 percent of the placebo group. Severe-GVHD-free survival was significantly improved: 93.2 percent with abatacept versus 82 percent with placebo.

The benefit of abatacept was most pronounced in the 7/8 arm of the study. Only 2.3 percent of patients given abatacept developed severe acute GVHD, versus 30.2 percent of historical controls. Rates of survival free of severe GVHD were 97.7 percent and 58.7 percent, respectively.

Leveling the playing field

The 7/8 group was important to include, says Kean. The ability to perform bone marrow transplants safely in this group opens up an option that didn’t exist before.

“Patients with donors matched on 7 of 8 HLA factors have previously had dismal outcomes,” she says. “Many oncologists won’t even consider these donors, and patients who only have 7/8 donors are often excluded from trials of new therapeutics. If we can make these transplants safer, we would have the ability to offer them to many more patients.”

That would be good news for people in non-white ethnic groups needing transplants, says Kean. Because of the complexity of their HLA genetics, they have much more difficulty than white patients in finding fully matched donors.

Inhibiting T cells, selectively

Abatacept works by suppressing the donor T cells that trigger acute GVHD, known as effector T cells. These cells need two signals to activate them. Abatacept blocks the second, or costimulatory signal; hence the technical term “T cell co-stimulation blockade.”

A detailed immunologic analysis, including RNA sequencing of patients’ blood, confirmed that abatacept controlled T cell activation.

While this kind of immune suppression could theoretically weaken people’s defenses against infections and the cancer itself, the study found no increase in severe infections or relapse in the patients with leukemia. This suggests that abatacept’s immune suppression effect may be selective for GVHD.

“We found that the T cells are prevented from attacking the host by causing acute GVHD, but they appear to retain their ability to fight leukemia,” says Kean. “This is impressive, given that these patients received an additional immunosuppressive drug. It’s like having your cake and eating it too.”

More trials underway

These positive results in patients with blood cancers have led to at least six new clinical trials of abatacept in patients receiving bone marrow transplant for severe aplastic anemia, sickle cell disease, beta thalassemia, and other diseases. The drug’s developer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, is pursuing formal FDA approval to expand the label of abatacept to include acute GVHD prevention.

Benjamin Watkins, MD, and Muna Qayed, MD, of Emory University, were co-first authors on the paper. Amelia Langston MD, of Emory University and John Horan MD, of Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s were co-senior authors with Kean. Watkins and Qayed report receiving grants and/or personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb during the course of the study and are named on pending patents.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CURE Childhood Cancer, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the American Cancer Society, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Learn more about the Stem Cell Transplant Program at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s.

Related Posts :

-

A big step toward curbing graft-vs.-host disease after bone marrow transplant

A drug used for rheumatoid arthritis has moved a step closer to FDA approval for a desperately needed new use. ...

-

Parsing the promise of inosine for neurogenic bladder

Spinal cord damage — whether from traumatic injury or conditions such as spina bifida — can have a profound impact on bladder ...

-

Unveiling the hidden impact of moyamoya disease: Brain injury without symptoms

Moyamoya disease — a rare, progressive condition that narrows the brain’s blood vessels — leads to an increased risk of stroke ...

-

Tough cookie: Steroid therapy helps Alessandra thrive with Diamond-Blackfan anemia

Two-year-old Alessandra is many things. She’s sweet, happy, curious, and, according to her parents, Ralph and Irma, a budding ...