Going ‘all in’ for Khori: New hope for congenital enteropathy

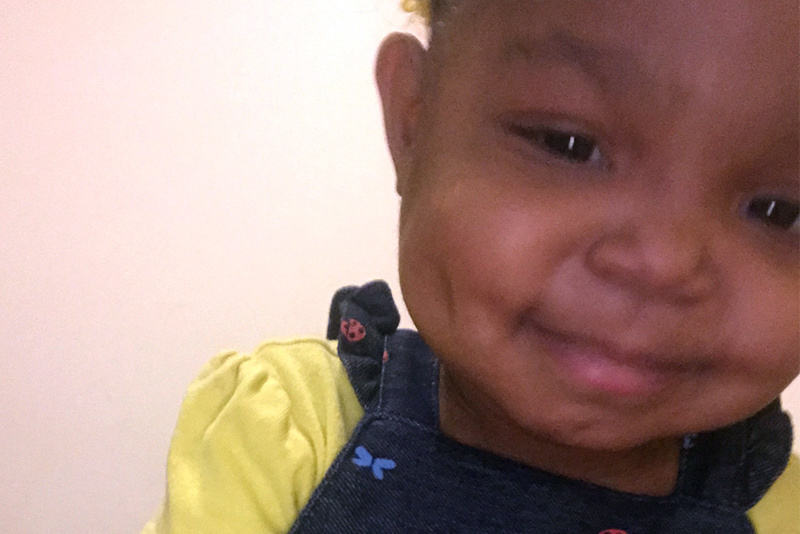

Khori LeBlanc is “one of the sassiest and sweetest kids you’ll ever meet,” says her mom, Bryanna Black. Her good mood even carries over to her many hospital visits, where she can be often be found practicing her “karate” moves on the way to an appointment. It’s a resilient attitude that has served her well in her young life. At just 3 years old, Khori has been through more than many adults.

Although Bryanna’s pregnancy and delivery were relatively uneventful, she became concerned shortly after Khori was born. “I knew something was wrong when she vomited every time I tried to feed her,” she remembers. She was initially diagnosed with pyloric atresia, which is a blockage in the lower part of the stomach.

Unraveling a genetic mystery

Yet her symptoms continued even after surgery to fix the problem. By the time Khori was 3 months old, she was still vomiting and experiencing chronic diarrhea. Eventually, clinicians at Our Lady of Lake Regional Medical Center near her home in Louisiana diagnosed her with a possible congenital enteropathy. This group of disorders, marked by unrelenting and untreatable diarrhea, usually has a genetic cause.

Khori’s physicians recommended she travel to the Congenital Enteropathy Program at Boston Children’s Hospital — one of the few centers in the world that specializes in these rare conditions — for further evaluation. The program’s clinicians are experienced in investigating genetic causes for severe diarrheal diseases. Bryanna was immediately interested. “When it comes to Khori, I’m all in,” she says. “I want learn about everything that might help her.”

Finding hope in research

In Boston, testing revealed that Khori has a mutation in her TTC7A gene, which can disrupt intestinal development and lead to disease. But the relief of having an answer was tempered by the harsh reality: Most children with TTC7A disease don’t survive past their second birthday. Although medication helped treat Khori’s symptoms, she experienced multiple infections and had trouble gaining weight. “We eventually began talking about palliative care,” says Bryanna. “I knew I needed to start preparing myself for that.”

Then she learned about an ongoing multicenter collaboration that Boston Children’s participates in. This ongoing research includes screening various FDA-approved drugs to see if they have potential for treating congenital enteropathies in children with certain genetic mutations (see sidebar below). Bryanna reached out to Khori’s physician in Boston, Dr. Jay Thiagarajah, who is the program’s co-director and also involved in this study. “My daughter needed a better quality of life,” she says. “If there was anything we could do to improve that, we needed to do it.”

Promising results

Based on his research using Khori’s own cells, Dr. Thiagarajah determined that Khori was a perfect candidate to start taking leflunomide, a medication used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in adults that shows promise for TTC7A deficiency. The treatment isn’t without side effects: It can lower white blood cell counts, a problem Khori is already prone to. But alternating courses of the drug with time off from it seems to help. “We’re finding a balance,” says Bryanna.

Khori is experiencing benefits, too. Since beginning to take leflunomide in March 2020, she’s gained weight and is able to drink milk with less vomiting and diarrhea. Her intestinal inflammation has also decreased dramatically. To track her progress, Dr. Thiagarajah works closely with her clinicians in Louisiana for seamless care. And while Bryanna knows the future remains uncertain, she’s optimistic: Khori recently hit another milestone by celebrating her third birthday.

“It’s hard not to dwell on the fact that your child may not live as long as you would like,” says Bryanna, who credits her faith, as well as Khori herself, with keeping her strong. “It’s very hard — but when you look your child and see that potential, nothing can stop you.”

Finding an answer in Khori’s own cells

Khori’s treatment is the result of an inspired collaboration between Dr. Thiagarajah’s lab at Boston Children’s and Dr. Aleixo Muise, a gastroenterologist at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. Dr. Muise and his team were in the process of screening various FDA-approved drugs on cells and then testing promising candidates in zebrafish engineered to have TTC7A mutations. One of the best candidates: leflunomide, a drug currently FDA- approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis.

At the same time, Dr. Thiagarajah was using Khori’s biopsied intestinal tissue to grow colonoids, “mini guts” that resembled her own colon. With these colonoids, he was able to test and study the effects of leflunomide in Khori’s own cells — and found that it could reverse come of the negative changes in them. Based on these results, Dr. Thiagarajah worked with Khori’s clinical team in Louisiana to start her on the treatment, a truly personalized approach.

“This is the first case of the drug being identified as a possible treatment for this genetic disorder,” says Dr. Thiagarajah. In addition to Khori, two other patients in the U.S. are taking leflunomide for this purpose with encouraging results.

Learn more about the Congenital Enteropathy Program.

Related Posts :

-

Against all odds: Mila's unique mutation, and her own custom drug

Ed. note: Mila passed away in February 2021, at age 10. The Mila’s Miracle Foundation continues to work to pave a ...

-

A perfect genetic hit: New gene mutation implicated in rare congenital diarrhea

When the 1-year-old boy arrived from overseas, he was relying on total parenteral nutrition — a way of bypassing the digestive ...

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...

-

Team spirit: How working with an allergy psychologist got Amber back to cheering

A bubbly high schooler with lots of friends and a passion for competitive cheerleading: On the surface, Amber’s life ...