New genetic test yields answer after family’s 10-year search

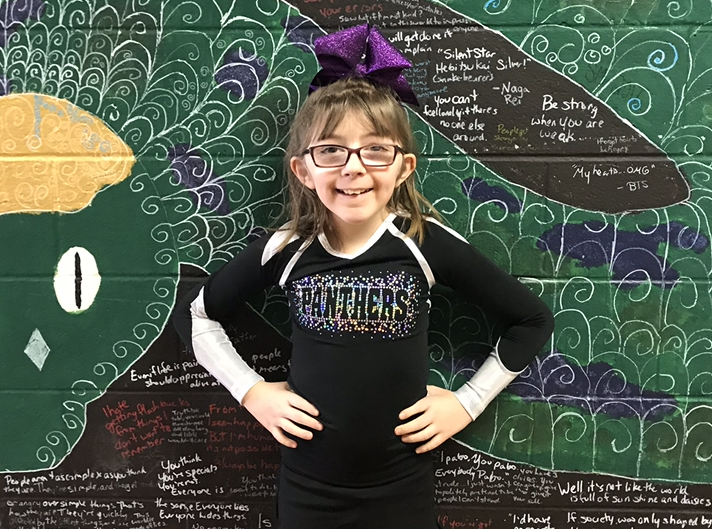

Kate Cole knew her daughter Lilly was different almost from the moment of birth. She was “a floppy baby,” lacking the strength and muscle tone her older sister had. She had trouble eating and was slow to gain weight. When she started on solid food, she often choked on it. She never really crawled and didn’t walk until age 2. Even then she was hesitant, because she had vision problems too. “And that made her afraid to push herself,” Kate recalls.

When Kate returned to work, Lilly spent her days at a day care center in a building where case workers for the state’s special needs program happened to work. Lilly caught their attention. “They said, ‘We don’t want to offend you, but something’s not exactly right,’” Kate says. “They wondered if she had cerebral palsy.”

But while her muscle weakness was the most obvious sign of a problem, Lilly had cognitive issues too. The family pediatrician referred her to a hospital in New Hampshire, about two hours east of their home in central Vermont. Doctors there diagnosed Lilly with global developmental delay, often a precursor to intellectual disability.

But Kate and her husband, Chris, wanted to know more. Why had this happened to their daughter? That question would send them on a 10-year search for answers — a search that would finally end with a powerful kind of genetic test administered at Boston Children’s Hospital. (See companion article: Panel urges new genetic test for neurodevelopmental disorders.)

‘You just get so frustrated’

In their quest to understand Lilly’s condition, the Coles would see orthopedists about Lilly’s muscles and bones, endocrinologists about her hormones, and neurologists about her brain and nerves, paying for many of the visits and lab tests out of their own pocket.

Eventually, Lilly was sent back to the New Hampshire hospital for genetic testing. They used a test called chromosomal microarray — the gold standard at the time. It found nothing.

“Everybody agreed there was something wrong, but nobody could pinpoint it,” Kate says. “You just get so frustrated. You’re like, ‘I know something’s wrong. I need to figure it out.’”

Taking matters into her own hands

At age 9, Lilly’s muscle problems intensified. “One day she couldn’t get herself up off the floor, because all her muscles were tightening and pulling,” Kate remembers. “She was screaming for five, six hours, literally not being able to make it stop. And I was looking at her and saying, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t know how to help you.’”

Finally, Kate decided to take matters into her own hands. She called Boston Children’s Hospital, without a referral, and asked if Lilly could be seen.

‘I’m going to get to the bottom of this’

When they arrived in April 2018, they were seen at the cerebral palsy clinic, then the orthopedics and physiatry departments. Next up was neurology, where they met Dr. Siddharth Srivastava.

“We must have sent him thousands of pages of documents,” Kate says. Yet Dr. Srivastava seemed to have read and absorbed them all. Instead of asking her to repeat Lilly’s story, as so many other doctors had, he merely asked a few questions to verify that he understood her case.

Dr. Srivastava prescribed a medication he thought might help with Lilly’s painful muscle spasms. “That was a life changer for us,” Kate says. “She never had that issue again.”

Even more important, Dr. Srivastava was committed to figuring out the cause of Lilly’s problems. “We spent a whole day there,” Kate says, “and at the end of it he said, ‘This is gonna drive me bananas. I’m going to get to the bottom of this.’”

A new kind of genetic test

Dr. Srivastava had a few thoughts about what might be causing Lilly’s condition. He took blood samples and ordered tests. They came back negative. But when Lilly returned six months later for a check-up, he suggested a kind of genetic testing called exome sequencing, which scans the most important part of a person’s genetic code for errors.

“In the last few years,” Dr. Srivastava says, “we’ve been turning more and more to exome sequencing, because it’s much better than older sequencing technologies at finding small errors in genes that can have big consequences for patients like Lilly.”

Months went by with no results. “I had no expectations, hope, or anything like that,” Kate says. “I just figured, we’ve always been told, ‘Sorry.’”

Finally, an answer

Then in late February, she heard unexpectedly from Dr. Srivastava. “He was on his way to work, and he called and said, ‘We’ve got something!’”

Two weeks later, Kate and her mother, a hospital nurse, met with Dr. Srivastava and got the answer the Cole family been pursuing for a decade. Lilly had been born with a mutation in a gene called SETD5, which is located on chromosome 3. The resulting condition, discovered only five years ago, has all the symptoms Lilly had been living with since birth. Finally, it all made sense.

“Like a lot of parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, the Coles had been living with a sense of guilt, wondering if this was something they passed on to Lilly,” says Jamie Love-Nichols, a genetic counselor at Boston Children’s. “Genetic conditions are never the fault of the parents, but in this case Kate was relieved to learn that Lilly’s condition was the result of a “de novo” variant in the SETD5 gene, meaning it didn’t come from her or her husband.”

“In layman’s terms,” Kate says, “it was just really bad luck.”

Even more important, Kate learned that, unlike some other neurodevelopmental disorders that lead to an early death or life in a wheelchair, Lilly’s SETD5-related disorder is not expected to worsen with time. “That may not seem like a big deal to some people,” Kate says. “But when you watch your child struggle every day for ten years and not know why, that’s huge.”

Looking ahead

“I’m glad exome sequencing was finally able to answer the questions the Coles have been pursuing for so long,” Dr. Srivastava says. “What we in the field of neurodevelopmental disorders need to do now is learn more about conditions like SETD5 and develop treatments that make life better for patients like Lilly.”

SETD5 is so new and rare that no treatments yet exist. But Kate hopes that may change with time. “The way science is advancing … she’s only 10, so even two or three years from now, who knows?”

In the meantime, the diagnosis is already having a positive impact on Lilly’s life. Because SETD5 is recognized as an intellectual disability, she will now be eligible for school support services she couldn’t get before. And the next time she comes Boston Children’s, Lilly will get a full cardiac work-up, because some patients with SETD5 go on to develop heart conditions. “Her heart seems fine now, but this way we can get ahead of something that potentially could be a problem later on,” Kate says.

Asked if she’d like to see exome sequencing made available to other families dealing with conditions like Lilly’s, Kate responds: “To have your blood drawn and get answers that could change your child’s life? What parent wouldn’t say: ‘Do it’?”

Learn more about exome sequencing.

Related Posts :

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...

-

Thanks to Carter and his family, people are talking about spastic paraplegia

Nine-year-old Carter may be the most devoted — and popular — sports fan in his Connecticut town. “He loves all sports,” ...

-

Genetic causes of congenital diarrhea and enteropathy come into focus

Congenital diarrheas and enteropathies are rare and devastating for infants and children. Treatments have consisted mainly of fluid and nutritional ...

-

Genomic sequencing transforms a life: Asa’s story

Asa Cibelli feels like he’s been reborn. The straight-A middle schooler plays basketball and football, does jiu jitsu, is ...