The polio outbreak of 1955: Lessons from an epidemic

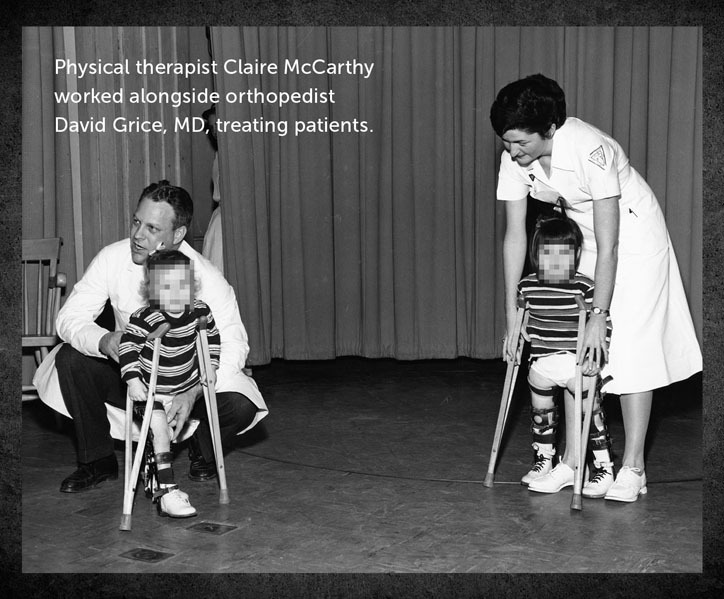

“This is going to be a tough year.” Claire McCarthy was a young physical therapist in early March 1955 when orthopedic surgeon Dr. David Grice, made this observation. At the time, Boston Children’s Hospital was the receiving center for adults and children with polio in New England. The hospital typically saw an upsurge in cases each summer. But in 1955, patients with polio started arriving earlier and in higher numbers than usual. It was the first sign of an outbreak that would go down in history.

Dr. Grice advised his team to prepare for a tough summer. “He kept reminding us to stay healthy. He told us to eat well, get enough rest, and take a vacation if we could,” McCarthy told Dr. Mark Rockoff, vice-chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine in a recent interview.

Polio versus COVID-19

In many ways, COVID-19 and polio present similar challenges. Like polio, COVID-19 is a highly contagious virus that can be deadly. But while COVID-19 enters the lungs through airborne particles, polio enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract, often via contaminated water. Despite their differences, both diseases resulted in outbreaks that tested health care workers — and brought out the best in Boston Children’s.

A major influx of polio patients

Massachusetts would report more than 2,000 cases of polio in the summer of 1955. Boston Children’s would admit more than 650 of them. At the peak of the outbreak, nearly 40 new cases arrived at the hospital each day. McCarthy recalls cars carrying sick children lined up along Longwood Avenue and Blackfan Street. “Physicians went out onto the street to evaluate patients,” she says. “Sometimes they would be out there until 10 at night, assessing patients with flashlights.”

Maintenance crews created a special area for emergency admissions in the lobby with plywood partitions. The hospital converted a division in its main building into an isolation ward. It dedicated entire floors to treating polio patients. Non-emergent surgeries were cancelled. By August, the hospital was over capacity, with polio accounting for 66 percent of its patients.

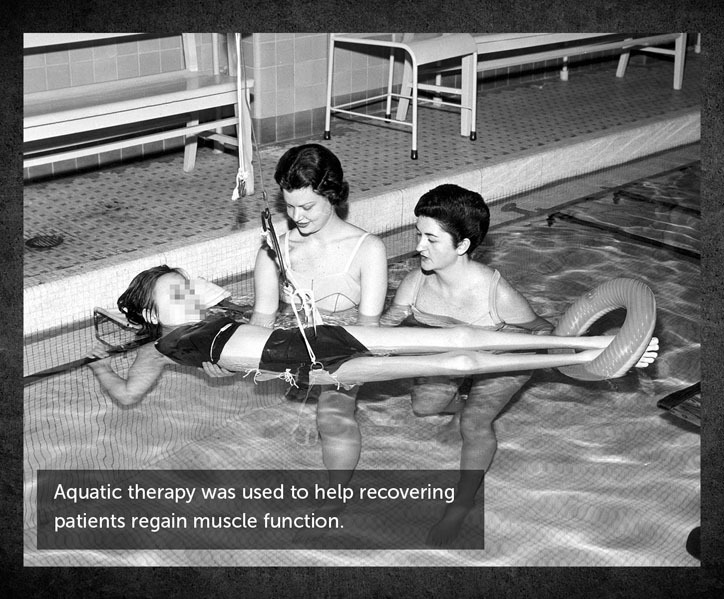

Many patients needed the assistance of an iron lung to breathe. For McCarthy, these were heart-wrenching cases. The children could not see their bodies or touch their own faces. And not being able to breathe on their own terrified them. Because of this, she empathizes with today’s clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients in respiratory distress. “When your patient is struggling to breathe, if you don’t have the right equipment, you feel like you’re not able to help them.”

Vaccination timelines

A breakthrough at Boston Children’s enabled development of the vaccine that would lead to the eradication of polio in the United States and most other parts of the world. Microbiologist John Enders, and his colleagues, Drs. Thomas Weller and Frederic Robbins unveiled a method for culturing poliovirus in human tissue samples in 1949. Jonas Salk’s injectable polio vaccine became publicly available six years later and Albert Sabin’s oral vaccine became available several years after that.

In light of today’s crisis, the time it took for the polio vaccines to be proven safe and effective is hard to imagine. “We all hope vaccine development, testing, and distribution can be accomplished much faster than in the polio era, so COVID-19 can also be relegated to history,” says Rockoff.

Hope for the end of the polio outbreak

No one knows for sure how the COVID-19 pandemic will play out. The history of the 1955 polio outbreak suggests that health care providers will continue to grapple with the disease long after the worst of the crisis has passed.

In September 1955, Boston Children’s then-president P.D. Howe wrote, “Hope grows that the end of this epidemic of 1955 may be in sight … But these things only mean that we are entering a new phase.” As he predicted, polio would leave its mark on many patients, and Boston Children’s would continue to care for them for years to come.

Get more answers about Boston Children’s response to COVID-19.

Related Posts :

-

No limitations: How Flora found answers for MOG antibody disease

Flora Ringler’s fifth birthday didn’t turn out as she had hoped. She and her family were vacationing in ...

-

What orthopedic trauma surgeons wish more parents knew about lawnmower injuries

Summer is full of delights: lemonade, ice cream, and fresh-cut grass to name a few. Unfortunately, the warmer months can ...

-

Partnering diet and intestinal microbes to protect against GI disease

Despite being an everyday necessity, nutrition is something of a black box. We know that many plant-based foods are good ...

-

‘They never stopped trying to figure out what was happening’: RyennAnne’s encephalitis journey

When 5-year-old RyennAnne Hurst developed a bad sore throat last summer, her doctor thought she might have strep and prescribed ...