What running mistakes lead to injury?

Running outside is a great opportunity to get some fresh air and, because it requires so little equipment, may be accessible when other forms of exercise are not.

At a lecture in February, specialists from the Division of Sports Medicine and The Micheli Center for Sports Injury Prevention described how running form – the way a runner moves their feet in relation to their knees, legs, and hips – can help or hinder their progress. A good grasp of the basics below may improve your form while reducing your risk of injury.

Stride length: A shorter stride is faster and safer

A long stride may feel like you’re really going for it, but overstriding – landing with your foot in front of your knee – actually slows you down. Your stance is less stable when your foot is out in front of you, so your upper body has to catch itself with every step. Your foot also spends more time in contact with the ground when you overstride. The difference may be a mere millisecond, but multiplied by thousands of steps per run, overstriding adds up to a measurable loss of speed.

Overstriding also increases your risk of injury. An overstriding leg is straighter and stiffer, which reduces your body’s ability to absorb the force of your landing. This can lead to shin, knee, and hip injuries. By contrast, landing with your foot below your knee is better form and better for your body.

Cadence: More steps, fewer injuries

Increasing your cadence, the number of steps you take per minute, can help correct overstriding and several other injury-provoking habits. “No matter how tall you are, how much you weigh, or how fast you run, ideal cadence is between 170 and 180 steps a minute,” says Dr. Pierre d’Hemecourt, longtime marathon runner, medical director of the Boston Marathon, and director of the Injured Runner Clinic. You may have to shorten your stride to take this many steps, which makes better use of the muscles in the back of your butt (your gluteal muscles).

Foot placement: Why you shouldn’t land on your heels

Shortening your stride can help you correct another running no-no: heel striking. Landing on your heel increases the impact on your bones, joints, and muscles. Landing on your middle foot is ideal.

Lean into your run

The position of your upper body has a ripple effect on the rest of your stride. Running with little or no forward lean, “running in the back seat,” as Dr. Kristin Whitney calls it, “limits your range of motion and doesn’t activate the strong muscles in your glutes,” says Dr. Whitney, a sports medicine specialist who cares for injured runners at Boston Children’s and in the medical tent of the Boston Marathon.

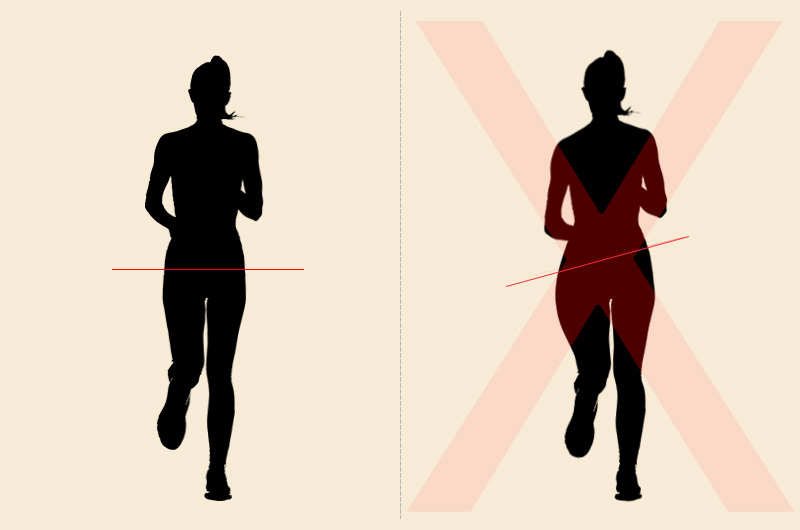

Hip alignment: Why you should run with level hips

When your foot comes off the ground, it’s easy to let your hip on that side drop slightly. This throws your body out of alignment. The knee of your “standing” leg is more likely to collapse inward and rotate internally when all your body weight is on that leg, putting excessive strain on the knees.

Training plans: A little math goes a long way

Ambitious goals, like deciding to run a marathon, tend to drive athletes to ramp up the length and intensity of their training too quickly without giving their bodies time to adjust. “Novice runners get injured when they start running too much, too soon,” says injury prevention specialist, Sara Collins. Experienced runners, on the other hand, may risk overuse injuries after years of repetitive stress on their bodies.

If you decide to train for a big race, increase your distance in small doses, 5 to 10 percent a week at most. In other words, if you are currently running 10 miles a week, add between a half mile and a mile to your weekly total. Pay attention to your body. Only add more distance when you have three successful runs without pain higher than 3 on a scale of 1-through-10 for the following 36 hours.

Take steps early to prevent running injuries

If you’re thinking of training for a marathon or other long run, Dr. Whitney suggests visiting an injury prevention specialist for a gait analysis. They can identify issues with your form and work with you to correct them. But be sure to start this process well in advance of race day. Particularly if you’ve been running a long time, your body will need time to learn and adjust to new running habits.

Training dos and don’ts for runners

- Do give yourself at least one or two days off from running a week.

- Do cross train. Strength training, stretching, and mobility exercises are good for you and your running.

- Do pay attention to your form. Consider having a gait analysis with an injury prevention specialist.

- Don’t make major changes to your form shortly before a big event.

- Don’t add too much distance too quickly.

Remember, every runner is different. Understanding your unique running form and developing a training regimen that works for you are key to your success.

Related

Avulsion fracture taps the brakes on a runner’s career

Learn more about the Injured Runner Clinic and Sports Medicine Division.

Related Posts :

-

Avulsion fracture taps the brakes on a runner’s races

By the time Will Benoit and his parents met Dr. Kristin Whitney, they all had a bad feeling about his ...

-

Five running exercises you can do at home

Unlike a lot of athletes, runners haven't had to take time off during COVID-19. In fact, a lot of athletes ...

-

Sports injuries: Why ignoring pain is bad for athletes

“No guts, no glory.” “No pain, no gain.” “Rub some dirt in it.” Sports clichés like these encourage young ...

-

When athletes push too hard: How to screen and when to refer

With the rise in the number and competitiveness of female athletes, overtraining has become a serious health risk for many ...