Saif looks ahead to life after spine surgery

Saif and his mother, Khawha Abbas, both had questions for Dr. Daniel Hedequist. For the past nine months, the family had lived in Boston while Saif underwent treatment for a severe spinal deformity. They were scheduled return to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that evening, but first, Saif wanted to know if he would be allowed to swim. When Dr. Hedequist answered “yes,” the 8-year-old made a diving motion with his hands and continued speaking. An interpreter for the family explained, “He wants to know if he can swim with his head under water.” His spine surgeon told him he could.

His mother’s questions centered on Saif’s safety. What if he fell? Dr. Hedequist assured her that Saif would be OK if he fell, although he should take it easy for a while. Saif would be going home in a brace from his chin to his torso. He would wear the brace for the next six months. “After that, his spine will be fully healed,” Dr. Hedequist assured Mrs. Abbas through an interpreter. “He’ll be able to do whatever he wants.”

Born with a severely dislocated spine

Saif was born with a congenital dislocation of his cervical spine and neurologic myelopathy (deterioration of spinal cord function due to compression). Several misaligned vertebrae in his neck pressed against his spinal cord, causing pain and restricting his mobility. He was delayed in both crawling and walking. When he eventually did begin to walk, his left leg was weak and sluggish due to the compression of his spinal cord. For his first seven years, he lived with severe neck pain and leg weakness.

Hoping to protect her youngest child from harm, Mrs. Abbas prohibited him from many of the rough and tumble activities of a typical boyhood. He became skilled at video games, but yearned to be physically active like his older brothers. He often accompanied his brothers to the gym, lifting one- or two-kilogram barbells while they worked out with heavier weights. “Even if he was born with a spine defect, he was not paralyzed and used to do a lot of normal things,” says his mother.

Crossing the globe for care

The first signs of Saif’s spinal deformity appeared when he was 3 months old. His neck appeared stiff and his parents observed only a flicker of movement in his left leg. Surgeons in the UAE recommended one unsatisfactory treatment after another. The family traveled to hospitals in Germany and Philadelphia, hoping to find a doctor who could relieve Saif’s pain and improve his mobility. But each encounter left them uncomfortable, so they kept looking.

“We heard the physicians and surgeons at Boston Children’s Hospital were very good,” says Mrs. Abbas. “Finally, we were able to come here.” Saif, his mother, and three of his five siblings met with Dr. Hedequist, chief of the Spine Division and co-director of the Complex Cervical Spine Program at Boston Children’s, for the first time in December 2018.

High stakes for a complex spine

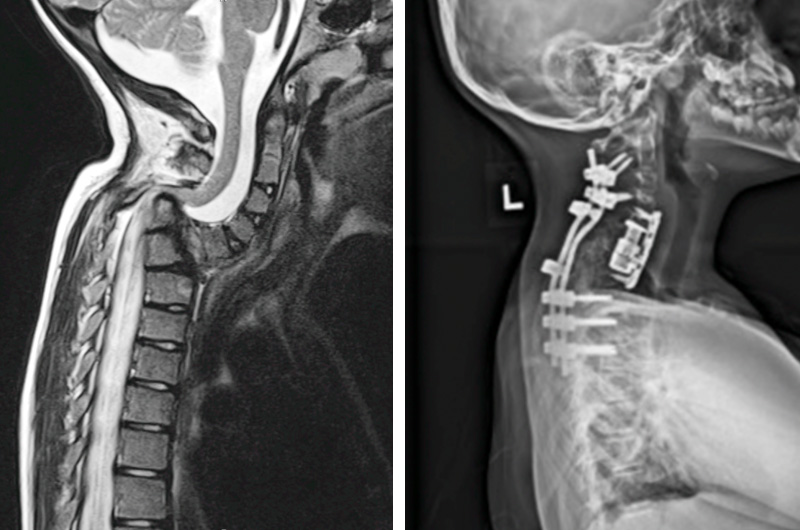

“In my twenty years’ experience, this was the most severe cervical spine deformity that we have seen in a child who still had neurologic function,” says Dr. Hedequist. “The amount of spinal cord compression we saw on his MRI made it hard to believe he was still walking.” Without surgery, Saif’s spinal cord would become further compressed until he eventually lost all function in his legs and would need to use a wheelchair.

Dr. Hedequist described a treatment that would take nine months. Saif would have to spend several months in the hospital as an inpatient. But he would only need one surgery. In the end, the unstable vertebrae in his cervical spine would be permanently realigned and held in place with titanium rods. Over time, his own healing capabilities would take over, fusing the previously collapsed vertebrae into a solid, stable bone. The family remembers Dr. Hedequist asking them, “What are you waiting for?”

Nine months of spine correction

Saif’s treatment began in January 2019 with halo-gravity traction. Dr. Hedequist attached a metal halo to Saif’s head with small pins. For four months, Saif spent his days and nights in the hospital as a pulley system attached to the halo slowly and gently lengthened his neck and released the pressure on his spinal cord.

Then it was time for a surgical procedure called a multiple-level vertebral column resection with spinal fusion. The procedure would make the realignment permanent and prevent any long-term deterioration of Saif’s spinal cord. Dr. Hedequist, along with the hospital’s chief of neurosurgery, Dr. Mark Proctor, removed sections from the misaligned vertebrae to create more room around the spinal cord. Dr. Hedequist then attached the instrumentation that would hold Saif’s vertebrae in place while his spine healed.

Saif spent May, June, and July in a halo-vest brace. This time, the halo was attached by rods to a hard, plastic vest that held his head in a fixed position. In early August, once his neck was sufficiently stable, the halo was removed. The family remained in Boston for one more month. Finally, Saif was strong enough to return home.

A lot of ambition to do many things

Saif will continue to wear a brace until February 2020. In the end, he will have less range of motion in his neck than his brothers and sisters, but greater stability and mobility than he’s ever had. His left leg will be strong. His chronic neck pain will be gone. He’ll be free to do whatever he wants to do.

When asked what activities he looked forward to, Saif and his older brother started speaking at once. “He wants to swim,” said the interpreter. “And get a bicycle.” His mother broke in, “He has a lot of ambition to do many things. Anything the adults do, he wants to do as well.” Saif nodded his head.

‘A miracle for us’

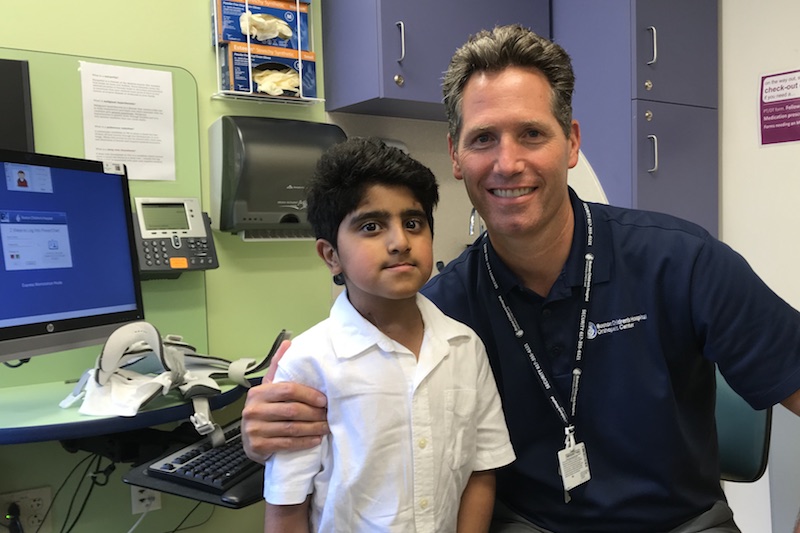

At his final appointment, after his mother thanked Dr. Hedequist for taking care of her son, Saif’s older brother asked if he could take a picture of Saif and Dr. Hedequist together. The family wanted everyone on the team to know how thankful they were for the fresh start Saif received at Boston Children’s. “We felt like God protected him in many ways,” said his mother. “Even getting to know Dr. Hedequist was a miracle for us.”

As the visit wound down, physician assistant Joseph Tremmel entered the room. Tremmel first met Saif at the outset of his treatment and had been involved in each stage of his care. With a solemn expression, Saif crossed the room to shake Tremmel’s hand. The interpreter did not need to explain. In his gesture, Saif bade farewell and assured everyone watching that he was on his way to a new life, the one his family had wanted him to have for so long.

Learn more about the Complex Cervical Spine Program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Related Posts :

-

Everli: Living her best life after atlantoaxial instability

When they travelled to the orphanage in China in early 2018, Shannon and Matt Gottschalk knew the toddler they hoped to ...

-

Gracie’s complex spine

Halloween 2018 was no ordinary ghouls’ day for Gracie Neef. She and both her parents dressed up as the witches from “...

-

Spinal fusion surgery during COVID-19

If things had gone according to plan, Jared Cohen would have had spinal fusion surgery during his April vacation. His ...

-

Scoliosis patients get a preview of spinal fusion surgery

“Patients are more at ease when they know what to expect,” says, Dr. Daniel Hedequist, chief of the Spine Division ...